This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Premium subscribers can sign up here to get the newsletter delivered every weekday. Standard subscribers can upgrade to Premium here, or explore all FT newsletters

Good morning. The US and UK struck the first Trump-era trade deal yesterday. It was underwhelming. In return for more buying of US farm goods and removing a tariff on US ethanol, the UK will be exempted from metal levies, and will enjoy lower tariffs on (a few) cars. Other promises and frameworks were laid out, without any timelines. Email us: [email protected] and [email protected].

How Berkshire has changed

Earlier this week we presented a sketch of Warren Buffett’s formula for success at Berkshire Hathaway. Buy safe, high-quality assets; fund them with low-cost, long-duration liabilities, many of them provided by a large, sophisticated insurance operation; use leverage but manage it carefully; and stick to your strategy for many decades, building a sterling reputation that acts as a powerful stabiliser for the business.

I think that’s a fair, if high-level, picture of Berkshire over the past 40 years or more. But while the model is stable, it is not static. Much has already been written (some of it by Buffett himself) about the change in what sort of companies Berkshire has invested in — from undervalued “cigar butts” in the early years to high-quality, stable franchises at fair prices as Berkshire grew.

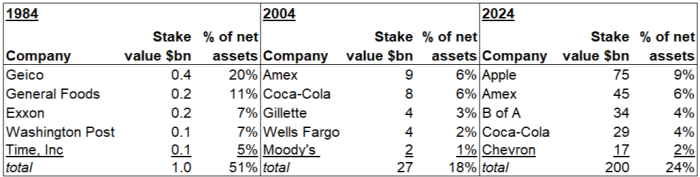

But what constitutes a stable high-quality franchise has changed over the years, and Berkshire has managed to change with it, by fits and starts. A way to see this is by looking at the biggest stocks in the company’s public equity portfolio. Here are the top five holdings from 1984, 2004 and 2024:

Staples (General Foods, Gillette, Coca-Cola) and finance (Geico, Amex, Bank of America) are a continuous theme. But publishing (Washington Post, Time) fell away and tech (Apple) rose. It’s important to note that Berkshire never, that I know of, nailed the timing of these transitions. It hardly left publishing at the top, got into tech too late by Buffett’s own admission, and got back into food in a big way (Kraft/Heinz) just as that industry lost its edge to the retailers and saw a structural decline in profitability. But the proof of the business model is that this didn’t matter, or didn’t as much as getting things right eventually, and continuously strengthening the boring, cash generative, wholly-owned insurance and industrial segments.

Another point of change: Berkshire appears to have reduced the amount of leverage it uses over the past 25 years. Here is a crude measure — assets net of cash divided into common equity:

Similarly, over the past 20 years or so, cash and short-term Treasuries as a proportion of total assets has risen, and has leapt in the past two years:

The jump in cash like assets is widely understood to reflect the fact that riskless short-term Treasuries now offer a real yield, and that there are few big assets at what Buffett and his team consider acceptable prices. They have been net sellers of stocks, notably Apple, for several years.

It is interesting to consider whether Berkshire’s leaders have decided to deleverage the company because their risk appetites have changed — or decided that, in a riskier world, deleveraging Berkshire is necessary to keep risk stable.

Taiwanese dollar, et al

This week saw a lot of movement in Asian currencies, particularly the Taiwanese dollar. It appreciated 6.5 per cent in just two days, its largest leap in decades. The Korean won, the Indonesian rupiah, the Thai baht and the Singapore dollar popped, as well:

This is a consequence of Donald Trump’s tariffs. The US’s appetite for foreign goods leaves its trade partners flush with dollars, which they invest in the US (though the direction of causality is not always clear; there is something of a “chicken or the egg” problem here). Taiwan, which runs a massive trade deficit with the US, is disproportionately invested in the US, relative to the size of its economy; we recommend reading Alphaville’s great series on this.

A large share of Taiwan’s US assets are owned by the island’s life insurance companies, who have taken advantage of the dollar’s strength and the Federal Reserve’s high rates to make what amounts to a carry trade: their assets are in stronger, high-yielding US dollars and Treasuries, and their policy liabilities are in weaker, low-yielding Taiwanese dollars. As the Alphaville pieces lay out, this trade has been under-hedged. The insurers do not own a lot of Taiwanese dollars, and their derivative hedges are too small to cover all the currency risk.

This week’s ructions mostly reflected an unwinding of these big dollar positions. The life insurers and other dollar-leveraged investors in Asia dashed for local currencies when it began to look like dollar weakness would be here to stay. Speculation probably played a role, too, particularly in Taiwan. Investors, aware of the mismatched liabilities, likely piled into the local currency. They might have also been inspired by rumours that the Central Bank of the Republic of China, Taiwan’s central bank — which facilitates the insurers currency hedges and is believed to have intervened in the currency in the past — would not intervene to keep the Taiwanese dollar down. The bank’s leadership might see a strong currency as a way to sweeten the Trump administration in trade negotiations, or think the currency will inevitably be stronger in the new tariff regime, and saw no point in getting in its way. The Taiwanese government denied the former, but the latter could be at play.

Things have settled down some, but most of the currencies have finished the week up against the dollar. This might be an early sign of a structural shift, which could be solidified by trade deals. From Daleep Singh, chief global economist at PGIM:

There are many Asian countries . . . that are eager to strike trade deals with the US. As part of those deals, there might be a greater tolerance of Asian currency appreciation [by those countries’ central banks] . . . Trade wars lead to capital wars. Asian currencies could be allowed to appreciate, while external surpluses in the region are allowed to narrow. That causes the US capital account surplus to decline, as there will be fewer overseas investors showing up at our Treasury auctions.

If Asian currencies appreciate meaningfully against the dollar, that has broad implications. US consumers will be poorer in real terms as imports from silicon chips to toys become more expensive. Treasury yields, all else being equal, will be higher. US risk assets could be cheaper, given a higher discount rate.

There are still tailwinds behind the dollar, however. As James Athey at Marlborough Group notes, other currency risks could be uncovered as the Asian currencies appreciate, especially if changes come suddenly or drive the currencies above the values that global rate differentials would imply. Companies and central banks might then intervene by buying dollars and Treasuries, or selling domestic currencies. Also, high US rates remain appealing. “The Fed is showing that it is not in a hurry to cut rates . . . and most other central banks are cutting,” said Mark Farrington at Farrington Consulting, an FX consultancy.

Trump’s tariffs imply less trade and fewer dollars flowing abroad, and, as a result, stronger foreign currencies and less Treasury purchases. For the time being, the US dollar still has a lot of privilege. But the rotation away from the dollar may have only just begun.

(Reiter)

One good read

No, globalisation didn’t hollow out the US middle class.

FT Unhedged podcast

Can’t get enough of Unhedged? Listen to our new podcast, for a 15-minute dive into the latest markets news and financial headlines, twice a week. Catch up on past editions of the newsletter here.